Introduction – SCC Data

This research was able to find patterns by using a data-driven approach to reading decisions written by the Supreme Court of Canada. The advantage of a data-driven method is that it allows for a “far reading” which can pick up high-level patterns that might get missed when reading a decision.

Broadly, this research investigated three different questions. It sought to understand (I) which words were used most frequently by the SCC, (II) how the length of decisions varied over time, and (III) the use of the “living tree” doctrine. Each of these questions will be accompanied by a graph.

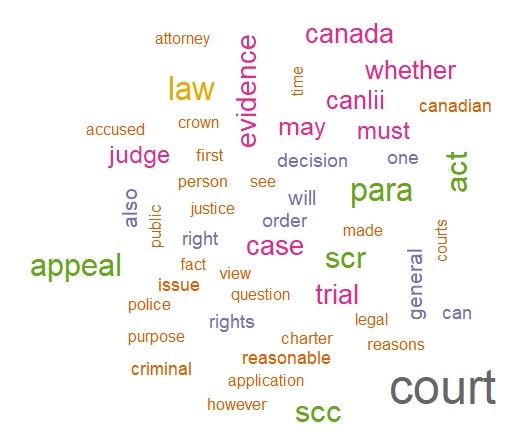

(I) Word Frequency

The below word cloud is a visualization of the words used in the 1000 most recent SCC decisions. The bigger the word, the more frequently it was used. We excluded stop words, or fillers, like “the”, “shall”, “he”, and “she”. In doing so, we uncovered some interesting patterns.

First, the term “law” is much bigger than the term “justice”. Law is used 33,291 times in the last 1000 cases while “justice” is used less than one-third of that amount with 10,871 occurrences. This supports the conclusion that our justice system prioritizes law over justice.

A second interesting pattern is that the word “reasonable” is the 26th most used word, being used 13,070 times, but the word “fair” ranks 566th. It is noteworthy that our justice system focuses more on ensuring that people act reasonably rather than fairly.

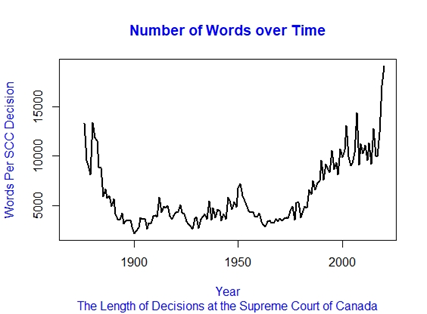

(II) Length of SCC Decisions Over Time

The SCC has demonstrated a clear pattern since the adoption of the Charter. The length of decisions has become much longer. Of note, early decisions include oral presentations which explain the early decline in the length of decisions.

As the graph below shows, the number of words used by the Supreme Court of Canada has increased markedly over the decades. Before the Charter, the Court averaged about 5000 words per judgment. In recent years, the Supreme Court of Canada has averaged closer to 10 000 words per decision.

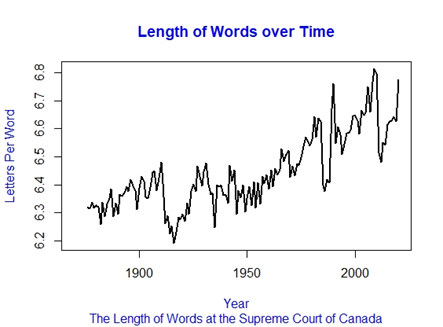

Meanwhile, this second graph shows the average word is now close to half a letter longer than it used to be. It has increased from about 6.2 letters earlier in the century to 6.7 letters recently. Together, these graphs show that the court is becoming more verbose.

There are two preliminary conclusions that can be drawn from these results. The first is that the Supreme Court of Canada is making more complex pronouncements about legal issues. This makes the law more nuanced, but also gives the Court a more important role vis-a-vis the legislature. The second is that legal decisions are getting longer. This means that it takes longer to understand them which makes them less accessible to non-lawyers.

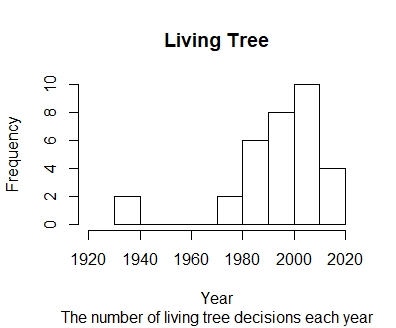

(III) The Living Tree Doctrine

The living tree doctrine is an important legal concept. It was first used to allow high courts to have a certain flexibility in their interpretation of the Constitution of 1867. For instance, in 1929 the UK Privy Council’s Edwards decision gave women the right to be Senators because the word “persons” which sometimes only included men now always included women. More recently, the doctrine was invoked by the SCC so that the word marriage included unions between same-sex couples.

Our analysis shows that the doctrine was only used 32 times by the Supreme Court since its inception in 1876. Each of these 32 mentions occurred since the Edwards decision.

The above graph demonstrates the pattern. The term living tree was used once in both 1930 and 1931 then disappeared until 1979. In 1979, the doctrine was re-introduced in response to political tumult in Québec. After this, the living tree began appearing more frequently, especially as a tool to interpret the Canadian Charter starting in 1982. After the Charter, the doctrine was used more frequently through 2012. Then, for whatever reason, it stopped being used. It was mentioned negatively in both 2018 and 2019, which makes this its longest hiatus since 1979.

The Takeaway

Data science methods enable us to find high-level patterns in all sorts of places. When applied to legal decisions, they help us better understand the considerations used by the Supreme Court of Canada. A “far-reading” helps lawyers take a step back and see judicial decisions with a bit more perspective.

This research was done by Nicolas Kasting using CanLii data with help from Professor Wolfgang Alschner at the University of Ottawa’s Faculty of Law.

Supreme Court of Canada